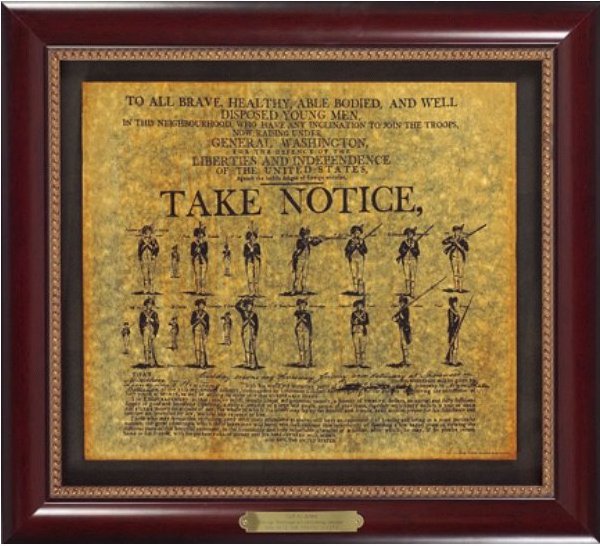

Framed Call to Arms document (14×17 image) with storyboard

$350.00

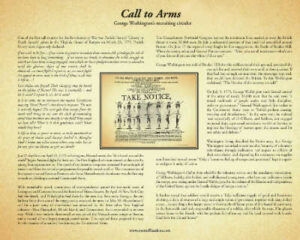

Framed 14×17 antiqued print of George Washington’s Call to Arms with 8×10 storyboard. The frame is 2-inch scooped beaded mahogany frame. The image is floated on a charcoal background — FREE SHIPPING on all orders over $50, $4.95 for orders under $25, and $9.95 for orders between $25 and $50. Please allow 3 weeks for production and shipping.

One of the first call to arms for the Revolutionary War was Patrick Henry’s “Liberty or Death Speech” given in the Virginia House of Burgess on March 23, 1775. Patrick Henry most vigorously declared:

If we wish to be free–if we mean to preserve inviolate those inestimable privileges for which we have been so long contending–if we mean not basely to abandon the noble struggle in which we have been so long engaged, and which we have pledged ourselves never to abandon until the glorious object of contest shall be obtained, we must fight! I repeat it, sir, we must fight! An appeal to arms and to the God of Hosts is all that is left us…!

Our chains are forged! Their clanging may be hears on the plains of Boston! The war is inevitable–and let it come! I repeat it, sir, let it come!

It is in vain, sir, to extenuate the matter. Gentlemen may cry, “Peace! Peace!”–but there is no peace. The ware is actually begun! The next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms! Our brethren are already in the field! Why stand we here idle? What is it that gentlemen wish? What would they have?

Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty, or give me death!

Just 27 days later, on April 19, 1774 in Lexington, Massachusetts, the “shot heard around the world” began America’s fight for freedom. The New England colonists reacted to this news by raising four separate armies. The speed of the American response stemmed from a decade of tensions and from the tentative preparations for possible armed conflict. The concentration of four separate armed forces at Boston under loose Massachusetts’s dominance was the first step towards establishing a national Continental Army.

With remarkable speed, committees of correspondence spread the dramatic news of Lexington and Concord beyond the borders of Massachusetts. By April 24 New York City had the details, and Philadelphia had them by the next day. Savannah, Georgia, the city farthest from the scene of the engagement, received the news on May 10. Massachusetts’ call for a joint army of observation was answered by the three other New England colonies–New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. Each responded in its own way. Within two months three small armies joined the Massachusetts troops at Boston, and a council of war began strategic coordination. This regional force prepared the way for the creation of a national institution, the Continental Army.

The Massachusetts Provincial Congress had set the minimum force needed to meet the British threat at some 30,000 men. By July a substantial portion of that total had assembled around Boston. On June 17 the regional army fought its first engagement, The Battle of Bunker Hill. When the enemy advanced General Putnam ordered: “Men, your are all marksmen–don’t one of you fire until you see the white of their eye.”

George Washington was told of Bunker Hill that the soldiers stood their ground, sustained the enemy’s fire and reserved their own until at close quarters. If they had had enough ammunition, the messenger reported, they would have defeated the British. To this Washington exclaimed, “The liberties of the country are safe!”

On July 3, 1775, George Washington took formal control of the army of nearly 20,000 men that he said were “a mixed multitude of people under very little discipline, order or government.” General Washington’s first orders to the Continental Army were to “forbid profane cursing, swearing and drunkenness.” In the same tone he ordered “and expect[ed] of all Officers, and Soldiers, not engaged on actual duty, a punctual attendance on divine Service, to implore the blessings of heaven upon the means used for our safety and defense.”

Washington Irving described the Patriot army that George Washington was asked to command as “an army of volunteers subordinate through inclination and respect to officers of their own choice, and depending for sustenance on supplies sent from their several towns.” Only a “common feeling of exasperated patriotism” kept the army together and gave it unity of action.

George Washington’s Call to Arms asked for the voluntary service, not the mandatory conscription, of “all brave, healthy, able-bodied, and well disposed young men…who have any inclination to join the troops, now raising under General Washington, for the defense of the liberties and independence of the United States, against the hostile designs of foreign enemies.”

It further stated that soldiers would receive a “fully sufficient supply of good and handsome clothing, a daily allowance of a large and ample ration of provisions, together with sixty dollars a year…in spending a few happy years in viewing the different parts of this beautiful continent, in the honorable and truly respectable character of a soldier, after which, he may, if he pleases return home to his friends, with his pockets full of money and his head covered with laurels. God Save the United States!”

These circulars were posted on trees or buildings where the recruiting meetings were to be held. The recruiters crossed out the dates and times when they changed locations.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.